Likely Stories

|

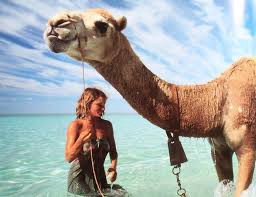

“That which is most systemic is most personal.” —Otto Scharmer

I know her, this young woman leading her four camels and black dog across the stark sandscapes of the Australian outback. She craves independence, solitude, nature, an irrational and reckless goal. She sets out to reach the ocean, walking 1700 miles across the outback, after shunning the advice of others. This is the true story of Robyn Davidson, which I now watch unfold in the movie Tracks. It is less than a week since I returned from Tacoma and my last ALIA Institute program, and my system is full of the ideas I heard there. Underneath all of the restlessness, optimism, and despair in our world, a new story is emerging. Or at least we hope it is. Sometimes we see it and feel it, in glimpses and pockets. It is a return to something that has been lost, an intuition of something we already know, at the place where our ancient selves see our pioneering new selves in the same mirror. This new story isn’t something to be believed. It can only be told through experience, through the voice that speaks our most personal truth. After the movie, I read interviews with Robyn Davidson, who says her journey of almost 40 years ago profoundly changed her life. For one thing, she became an author and a celebrity. She insists that she still doesn’t know why she set out on that journey or why it resonated so strongly for so many people. She doesn’t think her mother’s suicide when she was 11 played a direct role, even though the film’s director suggests a connection. But the effects of that trauma, and the ensuing separation from her father and beloved dog, are surely transparent to anyone who has struggled with the legacy of childhood wounding. When core bonds are broken, and especially if they are broken in violent or disturbing ways, the disconnect can lead to a lifetime of compensating, withdrawing, wandering, risk-taking, searching. I have witnessed how the search for a safer, more profound and dependable sense of connectedness can redirect the yearning for human intimacy towards a rawness of being, stark landscapes, animal bonds, aloneness under the night sky. Solitude can become one’s best friend and the vastness of nature one’s lover. A young life folds inward while pushing at the outer edges in search of wholenss. From that place, everyday social interaction seems petty, fickle, confusing, little more than noise. It is easy to romanticize this version of the survivor’s story. It contains seeds of truth and profundity, and it is noble in its courage and integrity. At the same time it is a story tinged with pride and haunted by an underlying shame of what is lacking, what has been broken, and the pain of separation. Brene Brown’s work popularized another level of healing that is possible when we are willing to be vulnerable. In the movie, Robyn’s journey takes her in this direction, as she comes to let down her guard, accept help, and grieve. In the instant when she finally and desperately calls out “I am so alone!” she comes more alive. At the end of her journey she arrives at the ocean, the archetypal mother, and dives in with joy and relief. After shunning and hating the photographer and reporters who want to document her adventure, she decides to work with them to share her story with the world. An emerging global story is mirrored in Robyn’s quest. As Charles Eisenstein reminds us, today’s institutions and systems, shaped in a time of linear rationality, individualism, and seemingly endless capitalist frontiers, perpetuate the myth of separateness and scarcity. This “old story” encourages each new generation and each “developing” country to compete, conquer, and consume, and this imperative is now placing our entire biosphere at risk. Even though it is killing us, this story is difficult to leave behind or even see when it is embedded in our most personal beliefs and in the social environment we call home. But at some point this story becomes old, dangerous, claustrophobic. We embark on a quest, not to change the world but to change the story that creates it. We leave many comforts behind, following the timeless tracks of the ancestors. We become more aboriginal, native to our planet. With few provisions except our personal compass and instinct, we venture into the wilds beyond shame, arrogance, and the illusion of isolation, and discover ourselves, each other, and our home anew.

0 Comments

|

AuthorSusan Szpakowski is co-initiator of Likely Stories. ArchivesCategories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed